In a rather unusual move, the Modi government refused to take a stand on Section 377 before a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court of India, which is currently examining the constitutional validity of the archaic penal law. A loosely worded provision of the Indian Penal Code, Section 377 has long been understood to criminalise same-sex sexual relationships, including consensual relationships between adults. In an affidavit filed on behalf of the Ministry of Home Affairs, the government informed the Supreme Court that the Union of India would leave the question of constitutionality of Section 377 to the “wisdom of the Court.’’

The government’s objectives are not difficult to understand. It does not want to be slammed homophobic in the mainstream national and international media. At the same time, the government does not want to alienate the largely conservative vote base of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party either. In light of several recent judgments, it is expected that the Court will, at the very least, read down Section 377, while leaving the larger questions regarding civil rights of queer citizens unresolved. When that happens, the government hopes, that it can walk away with a veneer of progressivism. And easily assuage the conservative BJP-faithfuls that it was the gay-loving, activist, “collegium Court’’ that should be blamed for the decision.

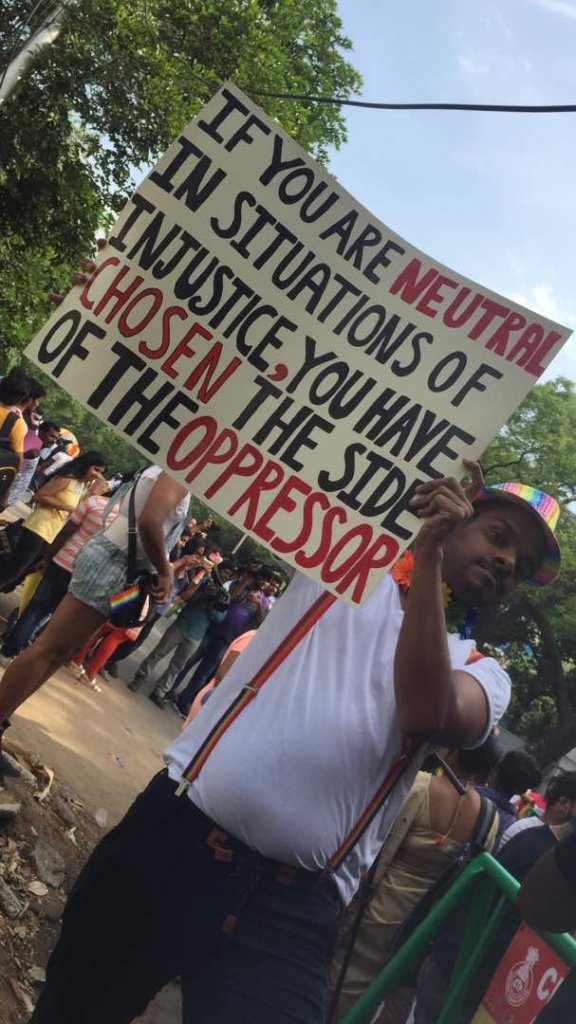

A placard at Chennai Rainbow Pride 2017 (Picture Credit: Moulee)

The government’s contrivance was revealed in paragraph 7 of the affidavit, where it said:

“If this Hon’ble Court is pleased to decide to examine any other question other than the constitutional validity of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, or to construe any other right in favour of or in respect of LGBTQ, the Union of India would like to file its detailed affidavit in reply…” (emphasis added).

Without saying so, the government is trying to portray Section 377 as an issue unrelated tothe rights of LGBTQ citizens, as if 377 had nothing to do with the their lives. This position is untenable. When a conduct inextricably associated with a particular community is criminalised, every member of that community is automatically branded a criminal, waiting to be convicted and carted off to a jail cell. To paraphrase the late Justice Antonin Scalia of the U.S. Supreme Court, a law that criminalises wearing turbans is a law that criminalises Sikhs.

The Court should not be fooled by the government’s affidavit, and should expose the government’s mendacity by compelling it to take a stand on the core Constitutional questions involved in this matter: Does Section 377 amount to discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation? Does Article 15 of the Constitution forbid discrimination on the basisof sexual orientation? While the government would like to characterise the Article 15 question as merely adjunct to the constitutionality of 377— belonging to the any-other-rights category— it is important to note that that is not the case. In fact, given the effects of 377 on the daily lives of queer people, the validity of 377 cannot be decided without considering these questions. These questions were considered by the Delhi Court in the Naz Foundation judgment. They are raised in the present petitions. The government cannot plead ignorance now and claim that the petitioners are springing a new argument beyond the scope of the present case. Moreover, Courts have long abandoned the doctrine that regarded the enumerated fundamental rights as isolated silos, water-tight compartments that are independent and disconnected from each other. Fully aware of this doctrinal development, why, then, would the government characterise the present case as a mere bedroom-rights case, and everything else as ‘other rights’?

It is already impossible to enforce Section 377 against relationships between consenting adults, for the simple reason that the government has no lawful means to invade citizens bedrooms. But then Section 377 was never about throwing consenting adults in jail. It was always about depriving queer citizens of their fundamental rights. It was about perpetuating prejudice, legitimising animus, and cloaking violence under the garb of law. The question of the constitutional validity of Section 377 is nothing other than the question of the right of queer citizens to be free from discrimination.

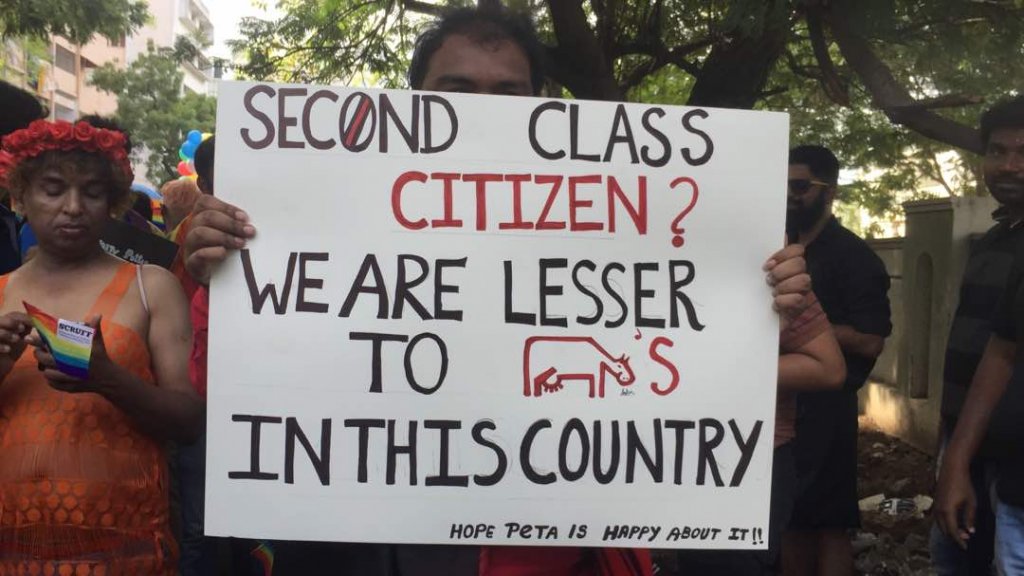

Poster at Chennai Rainbow Pride 2017 (Picture by: Moulee)

Our Constitution guarantees us the right to live with dignity, including the right to choose a partner. The Court has already said as much. Can it be said, then, that the right to life is confined to the bedroom? That our Constitution banishes queer citizens to islands of two? As Justice Albie Sachs, who served on the Constitutional Court of South Africa, so eloquently said:

While recognising the unique worth of each person, the Constitution does not presuppose that a holder of rights is as an isolated, lonely and abstract figure possessing a disembodied and socially disconnected self. It acknowledges thatpeople live in their bodies, their communities, their cultures, their places andtheir times. (emphasis added).

The petitioners’ are pleading the Court to recognise their right to live— openly and proudly, free from discrimination and harassment. The government knows that. And the Court must force the government to respond.

A change in criminal law is not going to accomplish the petitioners’ goals. It will be long before queer citizens can achieve the full promises of our Constitution. But that should not prompt the Court to issue the narrowest ruling the government seeks. It might serve us well to remember the words of the great American jurist Thurgood Marshall:

There’s very little truth in the old refrain that one cannot legislate equality. Laws not only provide concrete benefit, they can even change the hearts of men, some men anyhow, for good or evil.

Marshall was the grandson of a former slave. He witnessed firsthand how the law operated to deny African Americans their basic freedoms. He frequently defended innocent black Americans wrongly accused of capital crimes. He saw his clients’ being sent to the electric chair by racist prosecutors, juries and judges. He understood that the law did not just mean separate schools and separate water fountains; the law was violence. Yet, Thurgood Marshall could work to change the law, and confidently say that the law can change the hearts of people. Such is the power of law. And it is this power of law that our Supreme Court now holds. The Court should exercise it— with prudence, with understanding and with rigour.

One of the petitioners before the Supreme Court is a nineteen year old student. Today, through this affidavit, our government told him that they do not care about his freedom. The government told this young citizen that they are too embarrassed by his homosexuality to even talk about him. The government must be held to answer for its apathy.

Photo credit: Kshitij EM

In a note accompanying an 1837 draft of the Indian Penal Code, Thomas Babington

Macaulay wrote, (about Clauses 361 and 362, which later became Section 377 in the 1861

draft):

Clauses 361 and 362 relate to an odious class of offenses respecting which it is desirable that as little as possible should be said. We leave, without comment, to the judgment of his Lordship in Council the two clauses which we have provided for these offences. We are unwilling to insert, either in the text or in the

notes, anything which could give rise to public discussion on this revolting subject.

It is not that the Modi government today does not have a stand on Section 377. The

government does have a stand. And that stand is exactly the same as Lord Macaulay’s

stand in 1837—as little as possible should be said