Starting this May, I have launched an intersectionality tour. What this means is I will go around the world giving talks on what it means to be a complete human being, someone with a sense of humanity. If you’re interested in bringing me to your town, colleges, universities or workplace, contact me.

What’s the background for this tour? Well, talking about intersectionality has been the core of my activism, but it was not a journey I arrived at with the full knowledge of what it means.

Prior to my arriving on the shores of Europe (and by that, I mean London in 2007), I had only identified with few labels in my life; Yoruba, male and gay. While these labels are obscure or abstract, I was aware of my existence within those restrictions. I was also aware of the positives and negatives of those labels and I have used them both to my advantages just as equal ways they have brought me challenges.

Many people, including myself, have argued that labels are mere social constructs. However, saying that is not enough. We have to also acknowledge that they do not exist in isolation of what has been socially prescribed and they can have lasting impact on our lives, both negative and positive. So when we say “woman” and agree that this is a social construct, ignoring the challenges of what it means to be a woman within the construct of society controlled by patriarchy, we have defeated any act of activism we have in us.

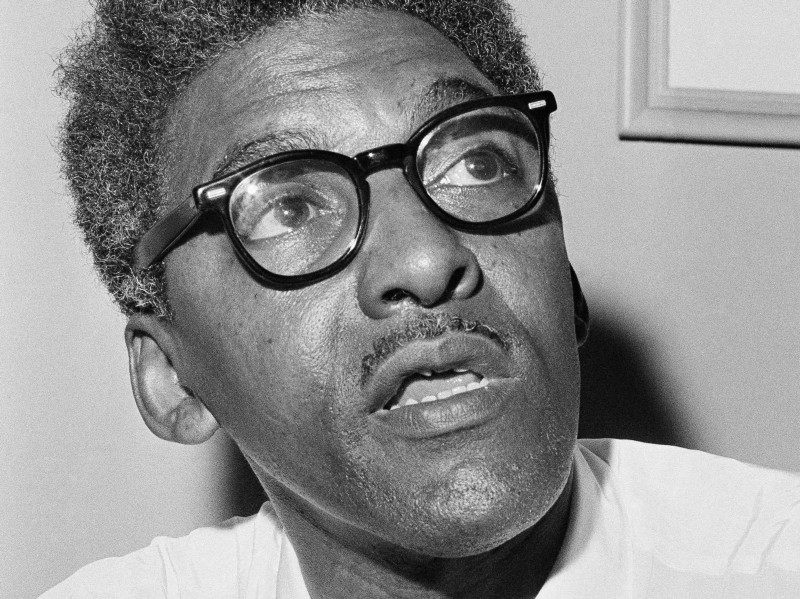

The beginning of my journey into the world of intersectionality started with my hero, Bayard Rustin. It was a quote from him that opened my eyes to the understanding of intersectionality and the importance and impact of social construct. A very good friend of mine gifted me “I must Resist” by Rustin for my birthday. Prior to this time, I had come across his video “Lost Prophet” on YouTube and that was the first time I realised that there was actually a black gay man at the heart of the civil rights movement.

In the series of letters Rustin wrote, I found many that addressed his sexuality as much as his race. He was a black gay man in the 60’s America navigating his way through the challenges of having two of the most hated identities of that era. I was taken aback by Rustin determination not to be ruffled by these realities. I wanted to know more and I wanted to situate myself within the framework of gayness and blackness, but then, I started having problem, as I was not black.

Bayard Rustin

Before arriving in the UK, I had spent 15 years of my 32 years in my birth country Nigeria being a Yoruba man, and then, at the age of 18, I fully discovered my gayness when I attended my first gay party in Lagos. While being a man in Nigeria is a good thing based on social construct and the benefits that comes with it, my gayness challenged these benefits and put me in a position where I experienced discrimination and persecutions on a daily basis.

The social currency that being a man gave me was quickly taken away from me for being gay. While being gay, I had to navigate my way around the social construct of what it means to be a man, how a man should act and the expectation of asserting my privilege as man.

It was tough and hard, and I struggled with it. Many times when I discussed this with my friends at the university, the conversations circled back around to, “it is a social construct,” but I wanted more. I wanted to know, how then do I exist within this construct without wanting to kill myself, trying to escape the assault or finding answers to the unanswered questions?

My question was compounded when upon arriving in the UK, I became black. In Nigeria, it was my ethnic group that mattered, not my skin colour. But here my skin colour mattered. I had to teach myself what it means to be black.

One of the places I learned this was at my first job at a fashion high street shop on Oxford Street in London. I was working as sale assistant. I arrived the UK in April and started the job in May. One day during my second week of work, I had a disagreement with one of my work colleagues who is a woman and white. During the exchange, she said I was shouting at her. I had no idea what she was talking about, what I realised was that, every time, I tried to tell her I was not shouting at her, she said I was shouting at her. At that point, I became agitated and realised that the more she said, “Stop shouting at me”, the more I raised my voice.

I became confused and had no idea what to do. Then the floor manager came, who also happened to be white and female. She called me into her office and asked why I was shouting at her. At this point I was lost for words, I broke down and started crying. I was crying not so much because I was angry, but because no one would believe that I was not shouting at her; I was only having a conversation with her. After the meeting with the floor manager, I was told to go home for the day.

It was when I started sharing this experience with black friends that I realised that, that singular experience was my installation to the blackness hall of pride. In less than four weeks of arriving in the UK, I have suddenly become black. I asked why they said that was my blackness moment? I didn’t understand it. I had never been black in my life and had no experience prior to that moment as to what it means to be black.

My friends explained to me that black assertiveness is shouting to white people, that the concept of “why are you shouting?” is a defense mechanism, employed by white people, consciously or not, to disempower black people. That the more they accused you of shouting, the more you are likely to shout. The other alternative is to keep quiet and that means subjugation.

Fast forward to a few years later, to November 2016. I had just married my husband and a picture of our marriage was all over the Internet. There were both many snide and approving messages, but one comment in particular struck me. This commenter said that as a famous black gay man, I have played into the stereotype of marrying a white person.

I never thought for the life of me that the colour of my love would be questioned, that someone would look at the picture of our happiness and see in it our races instead of our joy and happiness. Out of curiosity I probed to know who the person might be, I clicked on the bio and saw that he was a black man.

He was not alone. The racial dynamics of my relationship was a conversation online and a point of attack from both black and white people. It was also the object of ridicule from Nigerians who thought I married the man for papers rather than for love. This is ridiculous since I am actually a British citizen and my husband is Australian and we both live in London.

I have always lived my life openly as a means of encouraging others to be authentic to whom they are. This is the reason my HIV status has never been hidden. I never shy away from talking about it or other matters that some may say should stay private. However, as a gay man living with HIV, navigating my way around the gay dating world had been an excruciating one. It was full of rejection, while the people who wanted me usually either wanted me for the assumed size of my dick or for the fetish of my colour.

It was even harder trying to sustain a relationship in the face of strong prejudice. I remember once, my ex and I had a conversation on our first-year anniversary. It was supposed to be a celebratory evening, and it was, until he told me that his right-wing conservative family would be upset to find out he is gay (he had not come out at that time), but they would find it even harder to know he is dating a black man. Lastly, what would be the hardest of all for them would be to know that this so called black boyfriend of his is a refugee.

At that point I realised there is little or nothing I can do about social construct, it will forever rule my life.

Here I am, a black gay man, who is an immigrant living with HIV. How many more labels do I have to navigate in my life? How do I cope with the challenges that comes with being all this in one person?

As a public speaker, one of my biggest gifts is knowing how to make things work for me and I have had my fair share of that. My understanding of intersectionality has helped me to not only help myself, but to take others on the journey of social construct currency valuation.

The reality is, no matter how much I fight it, I will still remain a black gay man who is an immigrant living with HIV. I can either run into the cave and hide from humanity, or I can leverage that opportunity of being who I am to not just propel myself on a journey of self-fulfillment, but also take as many people with me as want to go.

Many people who are like me are name-called for being who they are, for things they cannot change about themselves, things that make them unique, beautiful, exceptional and more. There is no point hiding away from the reality of the challenging times we live in. It has become our collective responsibility to not just resist, but to be the change that we seek.

For these reasons, I am setting out on an intersectionality tour this month during which I will share my story and stories of many like me, those who understand and embrace their diversity and who challenge the danger of what Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie describes as “the single story.”

I am using this medium to reach out to YOU. Let’s make the intersectionality tour one that will go far and wide. If you want me to come and give a talk in your school, colleges, work place or town halls, feel free to get in touch with me.

Like Bayard Rustin once said, “We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers.” I have decided to be one for not just my community, but also my generation.

Republished with permission from the author’s Medium Post

- Why I am Starting the Intersectionality Tour - June 29, 2017