Even before the first Assamese film, Joymoti, was released in 1935, cinema as an art form had already acquainted itself with the concept of same-sex relationship. In a post World War I, censor-free Germany, a ‘social hygiene’ filmmaker Richard Oswald made Different from the Others (1919), an out-and-out homosexual themed film often hailed by film scholars and critics as the first of its kind in the world. The film garnered extreme reactions from the people and media. India got its first gay themed movie in Prem Kapoor’s Hindi language film Badnam Basti (1971). Regional language films followed suit soon. The Malayalam film Randu Penkuttikal (1978)paved the way by daring to showcase same-sex attraction at a time when the topic itself was a taboo in India. According to a snippet published in a leading regional newspaper, the first Assamese film to deal with the issue of same-sex relationship was a lesbian themed direct-to-video short film, released in 2006.

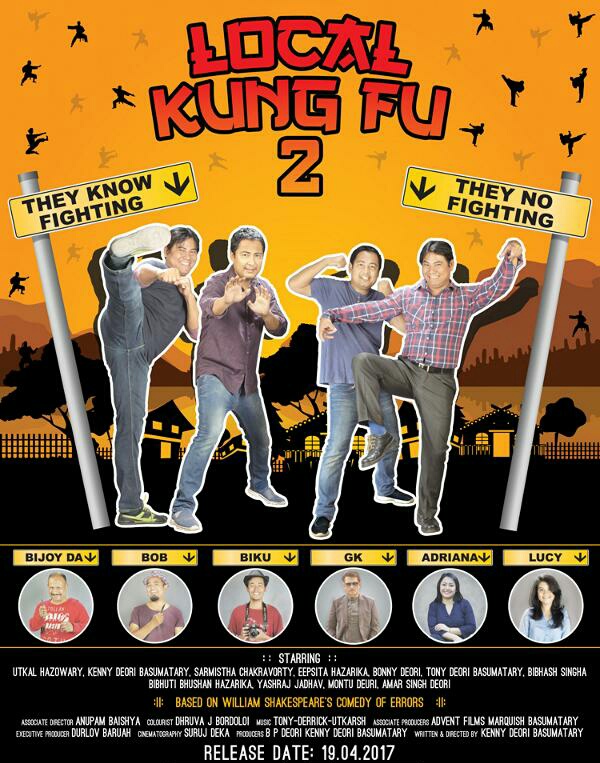

On a full length scale, the first Assamese feature film to have a homosexual character in its narrative was Kenny Basumatary’s Shakespeare inspired comedy Local Kung Fu 2 (2017). Based on William Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors, Local Kung Fu 2 doesn’t make a fuss about leading the way in showcasing a gay character on the silver screen. One of the USPs of the film is that Basumatary presented the homosexual character played by Utkal Hazowary just as he presented his other heterosexual characters. Like his filmmaking style, the homosexual character written by him is also free from clichés. In a review of the film in The Hindu, dated June 16, 2017, National Film award winning critic Namrata Joshi begins it with a discussion of the affirmative representation of the homosexual character. It is worth noting given that the makers didn’t promote the film piggybacking on its queer lead. The reason behind it can only be speculated but given the filmmaker’s maverick nature, it would be wrong to conjecture that he was worried about generating mixed response for the film prior to its release. The gay lead adds a layer of credibility to the story rather than simply being used as a comic relief when the going gets tough. The commendable aspect about the gay character is that he is open, respected in his job, and is mentally and physically thriving in a society – an ideal situation, not many Indian gay people in the real world can claim to be in. This is where the significance of positive representation of queer characters in films, comes in. Regional films have always been a medium to showcase local culture to a wider audience and to include a queer character as a flavour of local Assamese social milieu is a both a pragmatic and radical step forward.

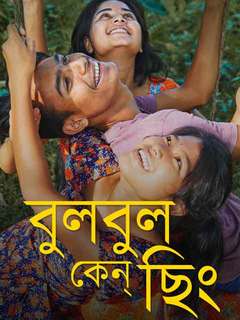

After getting a stupendous response to her film Village Rockstars (2017), director Rima Das decided to stick to her rural roots and tell a story of three village teenagers in her third feature film Bulbul Can Sing (2018). Bulbul, Boni and Sumon forms an inseparable trio of childhood friends going through the motions of life together. As they enter their teenage years, biology and society gets into a battle of one-upmanship and they undergo a painful yet inevitable coming-of-age. The character of Sumon/Sumu is of interest here as he is a boy who spends most of his time with his two ‘girl friends’ and hence is often subjected to catcalls and ridicules by his friends at school. His attraction towards another boy in his school is hardly the focus of attention in the story but it is impossible to overlook. Manoranjan Das who played the role of Sumon as organically as he could, walked away with many accolades for his performance including the Best Performance (Asian Feature Film Section) award at the 29th Singapore International Film Festival. More significantly, he won the Best Actor trophy at the Prag Cine Award (2019) – an award held annually, exclusively to celebrate the best in Assamese cinema – making him the first Assamese actor to win an award for portraying a queer character on-screen. With this victory he paved the way for Benjamin Daimary to step into the spotlight.

Benjamin Daimary, a first time screen actor, was 20 years old when he won a Jury Special Mention at the 67th National Film Awards for his uninhibited and unadulterated performance in Prakash Deka’s debut directorial feature Fireflies – Jonaki Porua (2020). On hindsight, it was a victory meant for the history books. To spell it out, an openly gay actor was for the first time honoured on a national level for portraying the role of a trans woman (male to female transgender) and that too for an Assamese language film. It not only broke the glass ceiling but also challenged the status quo of regional cinema vs. mainstream cinema. To top it off, Benjamin accepted the award from the honourable Vice President of India, wearing heels.

Benjamin’s victorious journey started when he won the Best Performance in a Lead Role at the 11th KASHISH Mumbai International Queer Film Festival (Virtual), 2020 edition. After being feted at the national and international levels, he finally tasted home grown success when he stepped into the shoes of his predecessor Manoranjan Das and got the Best Actor nod at the Prag Cine Award 2021, making him the first out and proud Assamese gay actor to bag the honour. This victory is a monumental proof that cinema in Assam is changing for the good.

Fireflies – Jonaki Porua tells the story of Jahnu’s (played by Benjamin Daimary) coming-of-age, ‘his’ struggle with gender dysphoria and the realization that life is not going to be easy for ‘him’ if ‘he’ chooses to express ‘his’ preferred sexual identity openly in a conservative society that he inhabits. ‘His’ affinity towards a feminine form of self-expression despite being assigned male at birth piques the curiosity of the villagers and some of ‘his’ family members. ‘He’ finds solace and support in ‘his’ elder sister Jumu (Bitopi Dutta) who identifies herself as a butch woman. She never had the agency or the opportunity to speak out for herself but she encourages Jahnu to listen to ‘his’ heart and ‘his’ body.

An openly gay actor was for the first time honoured on a national level for portraying the role of a trans woman (male to female transgender) and that too for an Assamese language film. It not only broke the glass ceiling but also challenged the status quo of regional cinema vs. mainstream cinema.

Jahnu’s love interest in the film Palash (Palash Mech) – an older gay man – is shown as living separately, away from the villagers. It can be interpreted as a sign of ostracism; highlighting the mindset that in a traditional rural Assamese social setting there is no place for homosexuality. The character of Palash was born out of the director Prakash Deka’s childhood experience of observing queer people and how the society treats them. Deka says, “when we were younger there was no concept of LGBTQIA+ as a community in India. We used to see and hear about such people who are considered different by the majority of the people. Some of them were even forced to marry by their family members to avoid the risk of suspicion. The character of Palash is someone who never had the courage to face the society due to self-hatred and self-shame inflicted upon him by the same society. So, he finds it comfortable to live at a safe distance away from the society that discriminates him”. The two outcasts – Jahnu and Palash – together form an instant connection and give the film its lighter and romantic moments. Jahnu’s life was never supposed to be easy but ‘he’ decides to change ‘his’ narrative by running away from home to join a gharana for transgender people. ‘He’ eventually transitions by undergoing gender reassignment surgery to embark on ‘his’ journey towards becoming a full-fledged female. Deka tried to stay as authentic as possible to the subject matter of his film by casting real transgender actor rather than have male actors appropriate the transgender community.

Fireflies – Jonaki Porua holds the distinction of being the first Assamese film to have a transgender lead, played by a gay actor and most importantly deals with the subject sensitively. Although the director had consciously cast real transgender people in his film but the act of casting a gay lead happened due to serendipity. Regarding the casting of Benjamin Daimary in the role of Jahnu, the director had no inkling that he was gay as it was only after the release of the film that he came out. “During the audition process, Benjamin could easily pull off the body language that we were looking for in the character of Jahnu and that is the reason why he was selected for the role”, Deka recollects.

Regarding the reception of the film by the local Assamese people, Prakash Deka says that, “my seniors from the industry forewarned me that I might get negative response from the audiences given the subject matter of the film but fortunately I have got only positive response from the Assamese people, so far. People belonging to the queer community have called me and thanked me personally and shed tears of joy to express their gratitude. People who used to bully queer people, at one point, called me up and expressed regret for their actions”. His words reiterate the fact that cinema is a powerful mass medium and can be harnessed accordingly. Fireflies – Jonaki Porua is produced by Milin Dutta, an Assamese transgender person and queer activist, who has founded the organizations Xukia and Anajori to work towards the betterment of the LGBTQIA+ community.

In 2019, Bhaskar Hazarika’s sophomore, genre-bending film Aamis (Ravening) shocked even his diehard admirers. According to American literary critic Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, understanding queer sexuality is “about trying to understand different kinds of sexual desire and how the culture defines them”. When we apply this logic to Hazarika’s Aamis, it proves to be a goldmine of queer cinematic mise-en-scène. On the primary level, the two main leads – Sumon (Arghadeep Baruah), a bachelor, and Nirmali (Lima Das), a married woman – not only breaks societal convention by engaging in a clandestine affair but they take it up a notch further by consuming bits of each other’s flesh as a means to consummate their relationship. They find a way to maintain the sanctity of their relationship through asexuality but at the same time breaks the cardinal rule of human civilization by literally devouring each other. In the film cannibalism – an antithesis to the idea of being human – is used as a positive metaphor of passion and desire.

On the secondary level, there is the non-verbal attraction of Elias, a varsity senior, towards a younger Sumon. Elias is a rare example of a Muslim gay character in Indian cinema. The attraction is shown in such a subtle and a blink-and-miss manner that the audience hardly gets a whiff of it. The actor Sagar Saurabh who played the role of Elias himself stated that the people who saw the film failed to recognize the homosexual aspect and context of his character. In one of the defining moments of the film, Sumon asks Elias to cut out a portion of flesh from his thigh area, giving it a both erotic and visceral appeal.

Coming back to the genre of short films, Bala – Essence of Love (2020), a lesbian themed short film, is the first one to venture into the queer territory since 2006. Focusing on the love affair between two teenage girls Jarita and Simi, the director Deepjyoti Deka tactfully highlights the predicament of young queer lovers. They are not able to speak their hearts out despite the repeal of the Section 377 of the IPC, as there is a social stigma still attached to the topic of same-sex love. The fear and shame induced by the negative social reaction makes queer youth susceptible to public taunt and render them emotionally unstable. In the epilogue of the film, the makers ask a straight-forward and poignant question – “when will the fear go?”

Simanta Phukan’s short film Tears of Rain – The Others (2021) tells a heart-wrenching story about a boy who is born biologically different from others. His widowed mother and his uncle try their best to ‘control’ and ‘change’ him but realizes that it is an impossible task as the boy keeps on embracing his true self with each passing day. Symbolically, the boy is nameless in the film as the society fails to recognize his ilk and to give them a fighting chance at a ‘normal’ life. The uncle in cahoots with the mother abandons him at a railway station and thus begins his journey towards becoming an independent transgender person. Arghadeep Baruah of Aamis fame plays the role of the grown-up transgender protagonist with the ease of a seasoned actor. The short film throws spotlight on the often neglected but the relevant issue of transgender hygiene facilities in the public space.

Joining the ever-growing list of thought provoking queer themed short films is Arindam Barooah’s yet to be released Wing One’s Way. It has already created positive buzz at film festivals around the globe. Also hoping to make a mark in the queer short film space is director duo Gaurav Boruah and Prajnyan Ballav Goswami’s Silence In The Wind. Earlier this year, Gaurav Boruah received a proud mention in Film Companion’s Hot List 2021 for the same, as recommended by actor Adil Hussain. Starring veteran actor Arun Nath and upcoming actor Kamal Lochan the short film delves deep into a father-son relationship; the former struggling to come to terms with the latter’s homosexuality. In 2020, the short made its way tothe World Human Rights Film Festival (USA), River to River Florence Indian Film Festival (Italy), and New York Indian Film Festival, not necessarily in that order.

When it comes to representing queer characters on-screen, the Assamese entertainment industry has utilized, more or less, all the available media platforms. After full length feature films and short films, the genre of music video/musical film too has jumped into the LGBTQIA+ bandwagon. Okolxoria (English – Loneliness), released on November 2020, is the first Assamese music video to feature two lesbian leads in its story telling. Adorned by Nilakshi Neog’s melodious voice and Ruhul Borbhuyan’s soulful direction, Okolxoria visually narrates a melancholic love poem about two village maidens. The music composer and lyricist of the song Pallab Talukdar in an interview to a news portal said that prior to casting Shabnam Nargish and Swastika Hazarika in the video they had discussions with other artistes and to their delight no one outright rejected the idea due to its subject matter. This is a sign of positive change of mindset.

On December 2020, Kothiyatolee – an indie music production, released their queer themed music video titled Aagontuk (English – Upcoming) featuring two young women in love. Towards the end of the video, the epilogue reads – “We are all queer, we just need our own time to realize our identities. Nature is not a taboo”. Both Okolxoria and Aagontuk haveset a new precedence for queer inclusion in the Assamese entertainment media.

It is hard to tell with certainty if the growing representation of queer characters on-screen is an indication of a change in the moral and social fabric of the Assamese society or just a product of our times where the queer identity has become a profitable capitalistic commodity. Such doubts and confusions should give way to clarity and empathy in film scholar Parthajit Baruah’s upcoming documentary feature The Children of God. In it, Baruah, is focusing his camera lens towards the struggles of queer teenagers. Its subject of focus is a transmasculine teenager – a girl who identifies as a boy and feels trapped inside the body of a girl. The conservative society in which she lives makes it difficult for her to speak her truth. About the documentary, Baruah says, “I have used Mother Nature as a character to give the protagonist of the documentary a psychological solace and to help her to see the world afresh”. The last five years or so have been an epoch-making era for Assamese cinema as far as queer representation is concerned. And given the influx of worldly-wise and liberal-minded millennial filmmakers into the art and science of film direction, it’s safe to say that the future of queer representation in Assamese cinema is in trustworthy hands.

P.S: I have in full consciousness used the pronouns he/his/him within single inverted commas instead of she/her and/or they/them/their to describe Jahnu’s character who identifies as a female and transitions towards the end of the film Fireflies – Jonaki Porua. The reason for it is to avoid any form of confusion for the readers who are not aware of the usage of queer appropriate pronouns. By doing so, I am not undermining the importance of using queer appropriate pronouns but giving the non-queer/binary readers an opportunity to understand queer issues better.

- Modern Love: Mumbai: The Good, the Bad and the Fine Balance between the two in Modern Lives and Relationships. - June 15, 2022

- Elite Season 5: As Queer as it Gets - April 19, 2022

- Cobalt Blue: A Very Timely Indian Queer Film - April 7, 2022